Mid-Year Health Check-Ins – Fit For Life

Give your team the reset they need with onsite wellness screening The middle of the year is the perfect time to check in, not just...

Read moreCurrent research from SafeWork Australia suggests job roles that are most at-risk include computer-based roles, call centre work, or jobs that require the operation of mobile and fixed plant machinery like trucks, boats, cranes, diggers or sitting at a control panel. Through a wider lens, these job roles represent 81% of Australia’s employed population, with 51% of these people reporting that they sit “often” or “all day” at work.

As a key strategy for increasing physical activity in the workplace and resultantly reducing occupational sitting, Active Office training offers a one-stop-shop for office-based physical activity tips and training.

Active Office is a physiotherapist-led program that seeks to actively improve worker health and wellness, whilst providing additional opportunities to the worker and workplace for improving office ergonomics, health and physical activity education, and reducing risk of injury and illness. With current Australian Government research advising that greater than 30 minutes of occupational sitting is likely to have a negative impact on your health, Active Office training is a very valuable opportunity for workplaces to develop new activity standards and maintain a healthier, happier and more productive workforce.

Active Office training is very multifactorial, despite having one clear and concise outcome in mind: improving health and wellness by reducing occupational sitting.

Active Office training sessions are built around the following principles:

Sedentary job roles involve long periods of sitting. This behaviour can lead to increased likelihood of developing sprain and strain injuries, as well as obesity and chronic diseases such as Type 2 Diabetes and Heart Disease. Additionally, there is even an increased mortality risk for workers that sit more than 11 hours per day – inclusive of sitting in the car or public transport when commuting to and from work.

Exercising before or after work doesn’t protect you from these health risks! A healthy workplace encourages people to move more and sit less.

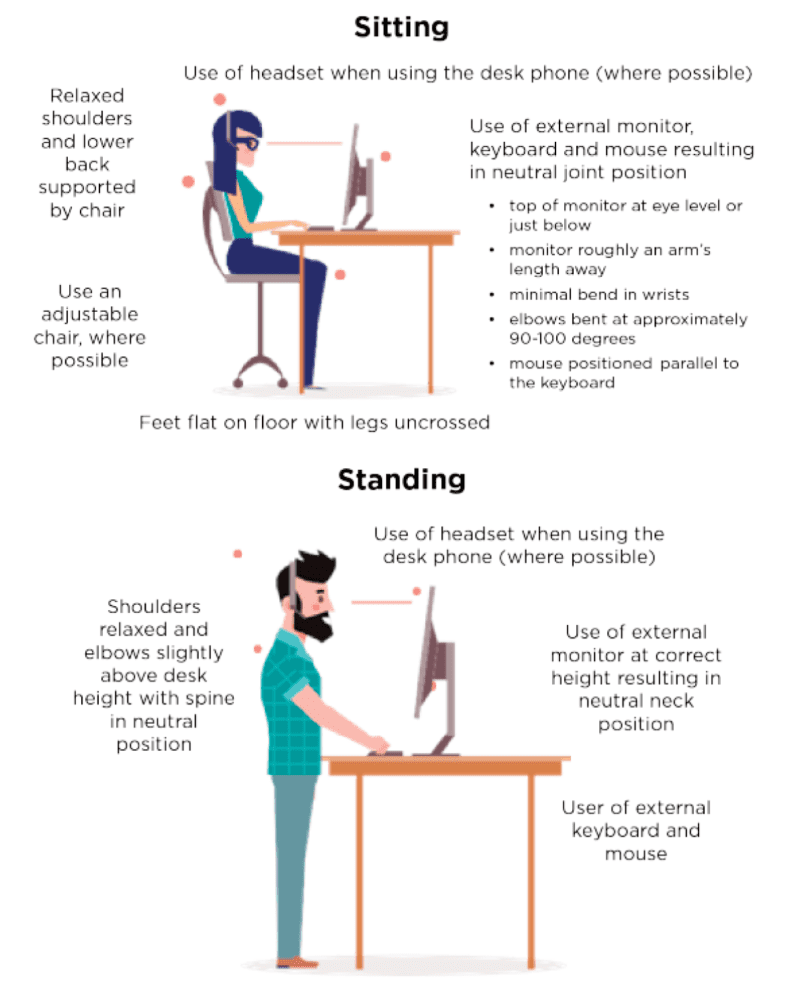

Current desk ergonomics standards are quite heavily investigated and generally well-established in research. However, having a clear understanding of how to effectively set up an office-based or home-based work station is the primary step in reducing a worker’s likelihood of injury and fatigue, and ultimately improve productivity.

Active Office training allows a workplace physiotherapist the in-person opportunity to analyse and modify workstations, whilst also teaching a workplace how to consistently maintain optimal ergonomic standards.

It is also paramount that workplaces aim to develop an office setting that encourages movement. Some easy examples of movement-invoking ergonomic office changes may include:

Once the workplace has been redesigned, it’s important to educate and create a healthy culture around staying active at work. Workplaces should encourage and support workers in creating a routine that schedules movement throughout the day – changing sitting posture every 30 minutes. Moving regularly will help reduce risks associated with sitting for long periods of time.

Additionally, workplaces can encourage workers to eat healthy lunches away from their desk – ideally in an outside setting – and even provide physical exercise options at the workplace.

Occupational sitting is a world-wide challenge, and with the constant development of new and growing technologies that aim to increase ease-of-work, the same benefit can be shared with workers to ensure their physical and mental wellbeing is upheld in the workplace.

Active Office training offers the advantage of knowing what the current health guidelines are for sedentary workers, but additionally, it offers the opportunity to learn about and access new technologies that provide workers with additional methods, devices and tools for reducing their occupational sitting time.

In addition to the aforementioned ergonomic options, exciting new technologies that may further assist workers and workplaces in becoming more active may include:

Physiotherapist-guided dynamic movement routines provide a myriad of mental and physical health benefits that are well researched and heavily supported by many companies with sedentary job roles and/or labour-heavy job roles.

As little as 10 minutes of mild-to-moderate intensity daily exercise has been shown to provide a 20% to 30% lower risk for premature all-cause mortality and incidence of many chronic diseases. The benefits of physical activity exhibit a dose-response relationship, meaning the higher the amount of physical activity, the greater the health benefits. However, the most unfit individuals have the potential for the greatest reduction in risk, even with small increases in physical activity. Given the significant health benefits afforded by physical activity, considerable efforts should be made to promote this vital component of health (McKinney et al. 2016).

Exercise can increase circulation and blood oxygenation, providing more energy to the body and reducing feelings of fatigue. This has been supported by multiple current studies suggesting that there is an association between physical activity and a reduced risk of experiencing feelings of low energy and fatigue when active adults were compared with sedentary peers (Puetz, T. W., 2006). Additionally, a 2014 study from Ellingson et al. investigated the difference in fatigue levels between active and sedentary women, and found that physical activity recommendations have benefits for energy and fatigue even when combined with an otherwise sedentary lifestyle.

A very recent paper from Rominger et al. (2022) found that regular physical activity has a positive impact on creative ideation, which supports the benefit of physical activity within more elementary cognitive functions such as executive control, memory, and attention. In support of this, Kim, J.'s 2015 study found that basic physical activity tasks like regularly squeezing a ball, resulted in increases in original and diverse ideas, in office-working adults.

Group-based physical activity creates opportunities for social interaction, team building and development of positive relationships between peers. Rosu et al. (2022) found that regular physical activity within a team improved conflict resolution, professional communication, problem solving, and a significant "breaking of barriers" between the collective members was facilitated. The participants expressed increased well-being, relaxation and pleasure of joint movement.

Physical activity releases endorphins that can reduce stress levels and improve general mood in workers, regardless of their industry. Chu et al. (2014) specifically explored workplace physical activity interventions and their effects on mental health outcomes and stress. It was shown that workplace physical activity and yoga programmes are associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms and anxiety, respectively.

In closing, there’s a significant list of health, wellbeing and creativity benefits that stem from daily, group-based exercise in the workplace. Active Office training provides a strong, evidence-based tool for staying active at work, to begin the journey in developing a happier, healthier and more productive team.

So reach out to Employ Health today to learn more about our Active Office program!

Give your team the reset they need with onsite wellness screening The middle of the year is the perfect time to check in, not just...

Read more

Why regular training is key to a safer, stronger workforce Manual handling injuries are one of the most common—and preventable—workplace hazards in Australia. Whether your...

Read more

How employers can support prevention, early detection, and healthier teams Diabetes is one of Australia’s fastest-growing chronic health conditions, and its impact reaches well into...

Read more

Every July, thousands of Australians take a break from alcohol to raise funds for people affected by cancer. But Dry July isn’t just a...

Read more

Safeguarding sensitive workplace data is no longer optional, it is essential. With cyber threats on the rise and regulatory changes looming, Australian businesses must...

Read more

Navigating the Rising Threat Landscape In today’s digital age, data security has become a paramount concern for Australian businesses. The increasing frequency and sophistication of...

Read more

What They Are and How to Manage Them in Your Workplace Mental health and wellbeing have become essential conversations in modern workplaces – not just...

Read more

Ways Your Business Can Make a Difference This June June is Women’s Health Month, a time to recognise, celebrate, and support the health and wellbeing...

Read more

May is Addiction Awareness Month—a time to shine a light on the habits and dependencies that affect the health, wellbeing, and performance of workers...

Read more

Manual handling is a part of everyday work across countless industries – from construction and warehousing to healthcare and hospitality. But it’s also one...

Read more

Drug and alcohol use in the workplace is more than just a safety issue—it’s a health, productivity, and culture concern. Having a structured workplace...

Read more

Quitting smoking is one of the most impactful health decisions a person can make—but it’s not easy to do alone. As a business, the...

Read moreCan’t find what you’re after?

View all articles